Hello. I’m Lou Blaser, and you’re reading We’re All Getting Older, where we explore the intentional (mid)life.

We are always on the way to somewhere. We’re always moving to some place or state of being that is different or “other than” where we are at the moment. Ideally, anyway; otherwise, we’d be stagnant, and who would want that?

Sometimes, that movement is by choice. But all too often, things happen that turn our ordinary lives upside down, and we’re forced or pushed to move to a new situation, whether we like it or not or before we are ready.

One thing I've come to understand is that with all these changes, grief is almost always present — even if the change is something we initiate ourselves or something we welcome.

If you think about it, change always involves the loss of something that was. And even in those “good riddance” scenarios, there tends to always be something that tugs, even if just a little bit.

• • •

A few weeks ago, I chatted with grief coach Charlene Lam on the Second Breaks podcast. Our conversation focused on the kind of grief that results from the loss of a loved one — perhaps the most emotionally difficult kind of grief there is.

Although we may not think about it this way, the death of a loved one is a change event.

We’re moving from a way of life in which we had a particular person in our world to a state of being in which they are no longer part of our lives. And the closer the person was to us and the more significant their role in our lives, the greater the loss we feel and the more significant the change we experience.

In their passing, we’re finding our footing, forming a new way of existing in a world they no longer inhabit. Life continues for us, but some change has been introduced and must be acknowledged.

We grieve not only for the loss but also for the part of our world that has fundamentally changed now that they are gone.

Sometimes, this may result in a change in our perspective or the way we engage with the world. Often, the death of a loved one means a loss of a dreamed future together, of assumed shared experiences, or of possibilities that can no longer be.

• • •

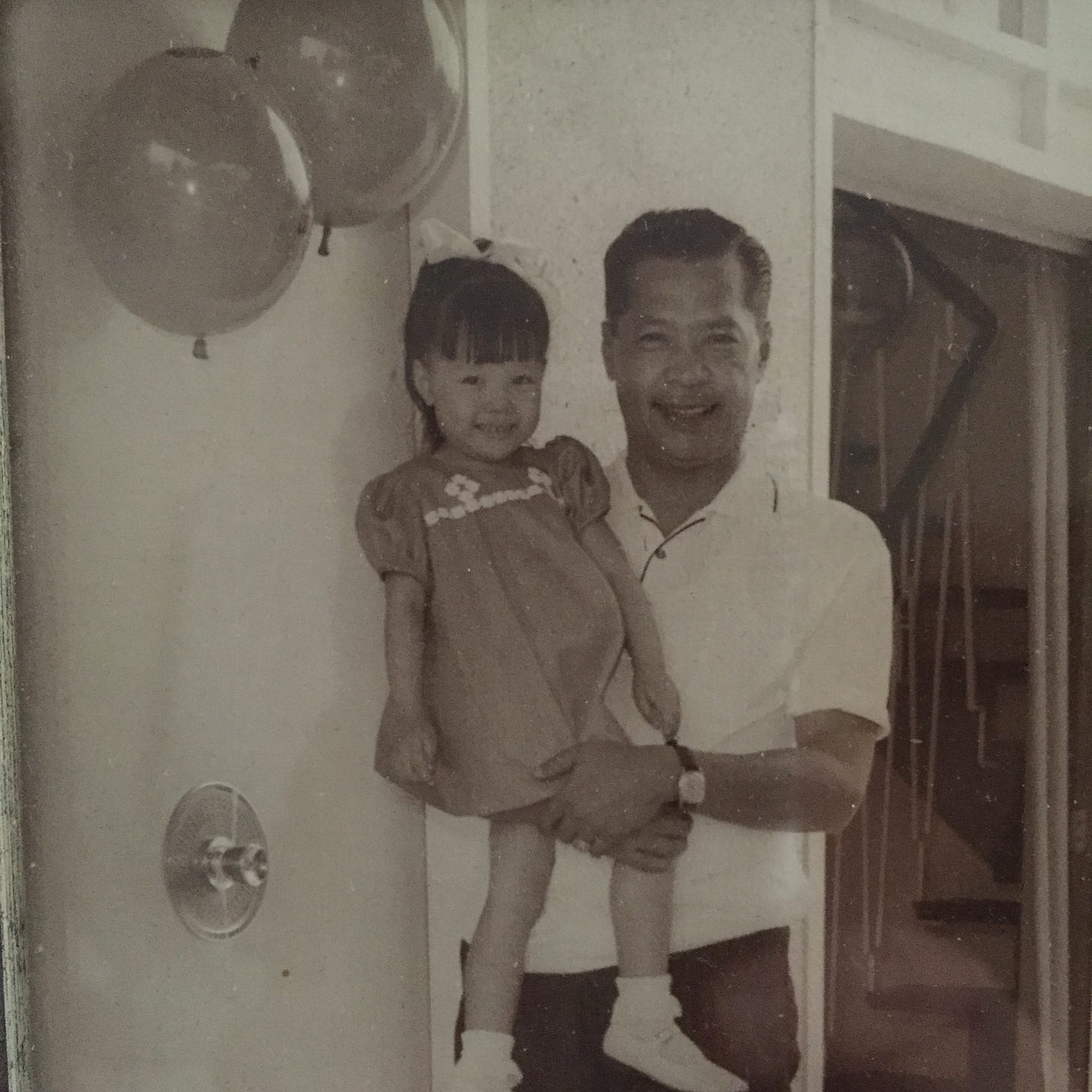

When my father passed away years ago, I remember waking up many mornings with a desire to talk to him about something that was happening in my life and feeling confused for a quick second as my brain struggled to remember that I couldn’t do that anymore… that the opportunity to converse with my dad and hear his perspective was forever gone. And it took me a while to get used to that new reality.

After my conversation with Charlene, I started thinking of grief in the context of another topic I discussed on the podcast a few weeks ago — liminal spaces. I realized that the state of grieving is one of those transitional phases we experience on the way to something different.

Liminal spaces are often characterized by ambiguity, open-ended statements, and uncertainty.

They are periods when the usual order of things is disrupted, and new possibilities emerge. Because of the inherent discomfort associated with them, we tend to rush the liminal periods in our lives, wanting things to be settled and “back in order” as quickly as possible.

In typical liminal behavior, we tend to hurry up our time of grief as well. We want to be done with it so we can “move on.” We want to be finished with the overwhelming sense of loss and the ache in our hearts so that we can go back to our normal — except, of course, it's not quite back to normal because the death of a loved one has fundamentally changed that state.

Regarding liminal spaces, I had said that there are “tasks to be done” while we’re in that space and that we would do ourselves a favor by not rushing to finish our liminal time. And in thinking about grieving as a liminal period in our lives, I stand by that statement.

Moving through the liminal space of grief involves a mix of emotional and practical tasks that help us weave the loss into our ongoing life story.

This liminal time is about reflecting, processing, and coming to terms.

In my conversation with Charlene, we discussed some things we could do to help here. For example, we might create a carefully curated memory box with items that remind us of our loved ones. Or write a heartfelt letter to them, which can help us process unresolved feelings.

In this liminal period, we’re doing the emotional work, adjusting to the change, and building a new sense of self and a new life that holds the absence of our person.

There’s a spectrum of care available to us.

What we need during our time of grief is different from person to person and specific to our nature and the way we process things in our lives.

“Spectrum of care ranges from medical professionals, grief coaches, free community support groups, friends and family. I think we would all do so much better when we know that there is the spectrum of care available to us and that they're all options.” — Charlene Lam

Coping with grief can involve seeking support from friends and family and finding comfort in activities like writing or art. Most importantly, it's about giving ourselves the grace to feel every emotion without judgment. Embracing this self-compassion can be incredibly healing, helping us maintain a lasting connection with our lost person while we continue to move forward in life.

Grief as a liminal space emphasizes the role of time in healing. Society can put pressure on us to “move on” quickly, to be back to normal, but the reality is that grief has its own timeline. It's crucial to allow ourselves the patience to experience and process grief, recognizing that it's a necessary transition phase.

Although painful, this mourning period can also be a profound time of personal growth and transformation for some.

We can only fully appreciate or recognize this if we give ourselves the time to sit with our grief.

• • •

Time spent grieving — however long that may be — is time in liminal space. It’s a transitional phase. It is fraught with emotional turmoil but also with the potential for profound personal growth — although this potential is often overlooked while experiencing pain.

If we can respect our grieving time as an essential liminal period, we can give ourselves the space to heal and transform. Grieving is not something to be rushed. It’s an essential process that helps us integrate loss into our lives and emerge with a new understanding of ourselves and our place in the world, albeit without our loved ones.

Astute observations, but I can't help but wonder, at what point does carrying grief become too long? Is there such a thing?

You are so right, in that there is grief in every change we experience…